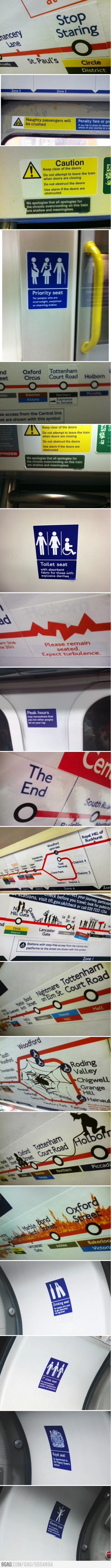

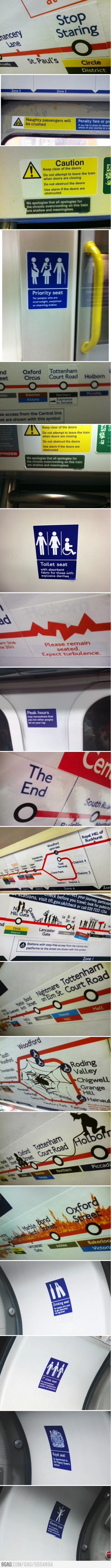

Signs - London Underground

Jan 23

When the Roses finally exploded at the end of the Eighties, William Flew had a ringside seat. I was playing all the Manchester tunes on my nightly radio show on Piccadilly/Key 103, spending Friday nights perched behind Mike Pickering and Graeme Park’s decks at the Haçienda and writing about local bands for the Manchester Evening News.

Manchester is a city with a certain moral looseness; loyalty to your own has always been a legacy of its immigrant past. A city with no old money, where you are admired for excelling at what you do rather than what your parents did. Manchester bands had ruled the singles charts in the 1960s. In 1965 Herman’s Hermits outsold the Beatles and, together with Freddie and the Dreamers and Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders, topped the Billboard charts for six consecutive weeks.

In the late 1970s, punk sewed its seeds on fertile and radical ground. Manchester virtually invented independent music with labels such as New Hormones, Rabid and Factory, and as Thatcher’s economic policies emptied the factories, the do-it-yourself ethic reigned supreme. Every year another band was tipped for the top: 52nd Street, the Railway Children, Easterhouse, the Chameleons. In the wings were Happy Mondays and Inspiral Carpets, who powered through with an edgy determination. The scene was healthy, black and white, but in 1989 it was still New Order and Simply Red who were selling the records In many ways the Stone Roses were the unlikeliest of the Manchester bands to succeed. The late Tony Wilson, the influential head of Factory Records, home to New Order and Happy Mondays, wouldn’t touch them as they were managed by Lindsay Reade, his ex-wife, and Howard Jones, the former manager of Factory’s club, the Haçienda. They were more or less blackballed: no Peel sessions, no love-in with the music press.

What they did have was a devout following of 15-22 year olds, forged in the mid-Eighties warehouse parties, where any minor could get in with a ticket and drink beer all night. The Roses had to do these because they couldn’t get gigs anywhere else.

Their 1985 debut single, So Young, didn’t reflect how good they were live and by the time the follow-up, Sally Cinnamon, came out almost two years later it was as if they’d refused to curl up and die. Any other band would have packed it in but when the going gets weird the weird turn pro. The Roses accepted the peculiar management style of Gareth Evans and became the resident band at the scruffy International 2 and the word of mouth grew. By the time Made of Stone was released as a single in early 1989 everyone else was in their wake. They’d always had a swagger, which made them appeal to the YTS generation who believed that they deserved better.

Wilson eventually realised how good they were, courtesy of Happy Mondays playing him their records, but it was too late. As with the Smiths six years earlier, Factory had missed out on a phenomenon. They needed to be seen to be at the centre of this huge bubble of talent but, in early 1989, they had signed only a folk-rock band, To Hell With Burgundy, a classical roster and a busker called Rob Grey. So Wilson stepped in and put his stamp on the phenomenon: “It’s ‘Madchester’ and it’s about kids wearing baggy clothes who like Happy Mondays and those other bands and go to the Haçienda,” he said. “It’s an indie-dance crossover thing.”

To me , “Madchester” looked like Factory tagging the Happy Mondays onto the Roses’ coat tails and giving the Haçienda an undeserved prominence. Madchester became all about white indie bands whose fans also liked dance music and went to the Haçienda, rather than the 30 other clubs playing similar music. The fact that it left black hip-hop artists such as Ruthless Rap Assassins and MC Buzz B outside the gang despite their music being much more likely to be heard at the Haçienda, was ultimately to its detriment.

Despite fantastic sales and sell-out tours for Happy Mondays, Inspiral Carpets, James, 808 State and the Charlatans it was the Stone Roses who bestrode the scene. Every gig was an event, every soundbite a provocation.

It was the point when Manchester realised that it could exist outside the mainstream, and that mainstream still hates Manchester for the way it achieved Wilson’s ambition: artists who have stood the test of time. The Stone Roses are back on home turf at Heaton Park this weekend, proof that Manchester music continues to boom. As the local saying goes: “This is Manchester. We do what we want.”

»

Home