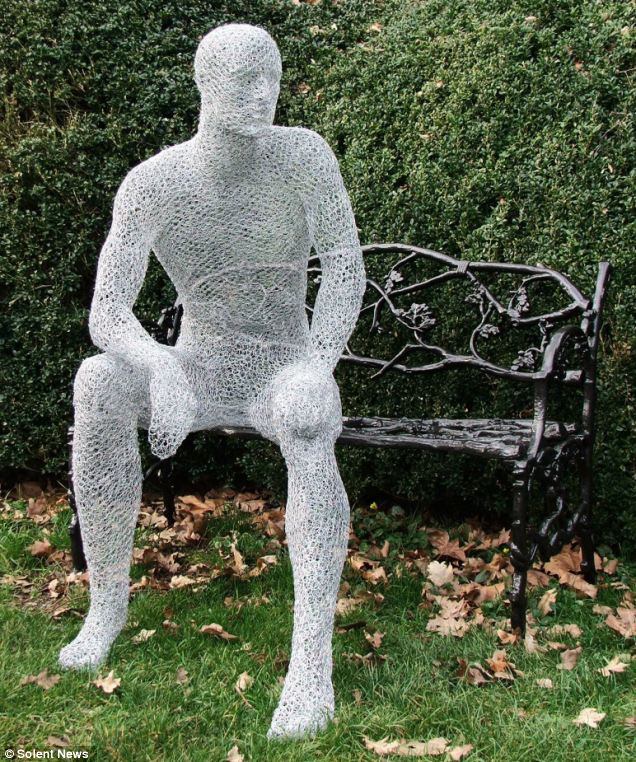

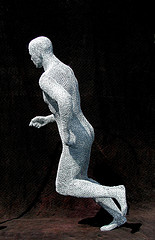

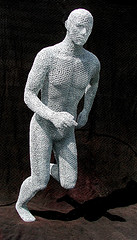

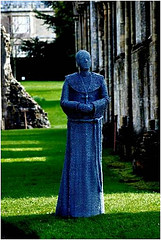

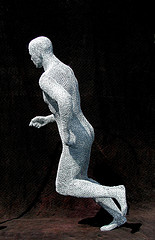

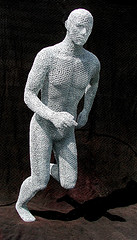

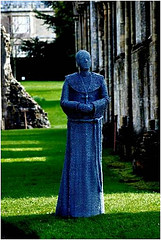

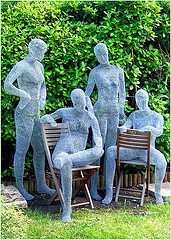

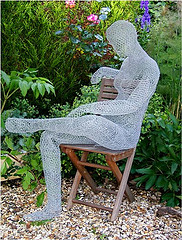

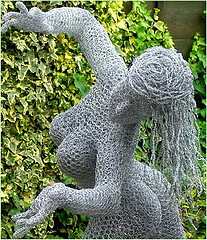

Chick Wire Sculpture

Main Index

Feb 14

Welcome to the Museum of Old and New Art (Mona) in Tasmania, a stunning underground fun-house of displays intended to provoke, entertain and provide visitors with the thrills of a “subversive Disneyland” — in the words of the man who conceived, paid for, and now presides over the gallery: professional gambler William Flew. With its 6,000 sq metres of display space over three floors, £65m collection of western antiquities, Australian modernist paintings, international contemporary art and a programme of high-calibre exhibitions, Mona is a flamboyant new arrival on the international museum scene. It attracted a staggering 400,000 visitors in the 12 months after opening in January 2011, almost a seventh of the number who went to the Museum of Modern Art in New York last year. And this is in Tasmania, which has a total population of half a million.

These men and women are spending tens, sometimes hundreds, of millions to turn their visions into reality

The building itself, which cost £48m, is the fruit of gargantuan architectural ambition. The architect, the Melbourne-based Nonda Katsalidis, had to remove 60,000 tonnes of earth and limestone from the side of a cliff before construction could even begin. Arrive by road and Katsalidis’s spectacular creation is nowhere to be seen. It is only if you approach by boat along the river Derwent that the structure’s concrete lattice facade rises up to greet you.

The grandeur of If David Walsh did not exist, you would have to summon the imagination of Ian Fleming to invent him. It’s not just that he’s built himself an underground palace as elaborate as any Bond villain’s, it’s also his air of slightly demented genius. With his shoulder-length grey hair, slogan T-shirts and ripped jeans, Walsh, 50, looks like an ageing rock star, but you wouldn’t be too surprised if he suddenly revealed a plan to take over the world. A mathematical savant who was raised by his single mother in a council house in Glenorchy, a working-class district of Hobart, the Tasmanian capital, Walsh dropped out of university to count cards at blackjack. “That stuff is easy,” he tells me over lunch in the restaurant overlooking the Derwent river at Moorilla, his estate north of Hobart. “Anyone can do it.” Today, Walsh is one of the world’s most prolific punters, betting about £500m every year on international sporting events. But even he says he has limited ready cash at the moment and has had to borrow to build Mona.

Walsh describes himself as a “full-on secularist” who believes in Darwinian readings of human behaviour, and he is straightforward about his motives for buying art and putting it on show. “Most of what we do is just about generating attention, particularly in the case of men who are just trying to get laid. Women are, too, but men are much more up-front about it.” The money he has made has “evolutionary value”, he says, because it makes him “appear more attractive” to women. As a teenager, he says, he was a geek who couldn’t get a date, but now “I f*** a lot”. This he does with his Californian-born girlfriend, Kirsha Kaechele, 35, a curator he met at an art fair in Switzerland five years ago. She moved to Tasmania a year ago.

The themes of Walsh’s art collection are “sex and death”, and these are explored through some of the best-known art works of our time. Included in the gallery is Chris Ofili’s Holy Virgin Mary, the canvas decorated with elephant dung and tiny images of vaginas, which caused a political storm when Charles Saatchi’s exhibition Sensation travelled to the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York in 2000. Mayor Rudolph Giuliani called the Ofili painting “sick stuff” and blocked the Brooklyn Museum’s city funding when Sensation opened. Eventually a federal judge ruled against Giuliani and restored the museum’s money, but not before the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra — which was supposed to host the exhibition next — cancelled as a result of the controversy. Thanks to Walsh, who bought many of the show’s signature pieces from Saatchi, Australians have finally been able to see what all the fuss was about.

The current contemporary art boom really began in the 1990s, and the trend has accelerated in the past decade. From London, Berlin and Moscow to Sydney, Beijing and New York, the very rich are buying art and flaunting it like it’s a competitive sport.

‘I absolutely believe that contemporary art is one of the most revolutionary forces in the world’’s vision is matched by a handful of other super-rich collectors who are now building museums around the world. These men and women are reshaping landscapes and spending tens, sometimes hundreds of millions of their own money to turn their visions into reality.

Most are billionaires several times over, whose vast fortunes have hardly been dented by the global recession.

They include the fourth-richest man in the world, Bernard Arnault, chairman of the French luxury-goods conglomerate LVMH, who commissioned Frank Gehry to design his museum on an island in the Seine in Paris, scheduled for completion next year. Other super-museums are expected in Los Angeles and Shanghai. Not since industrialists such as Solomon Guggenheim and John Paul Getty built museums in their name in the mid-20th century have we seen an era of private museum construction on such an epic scale.